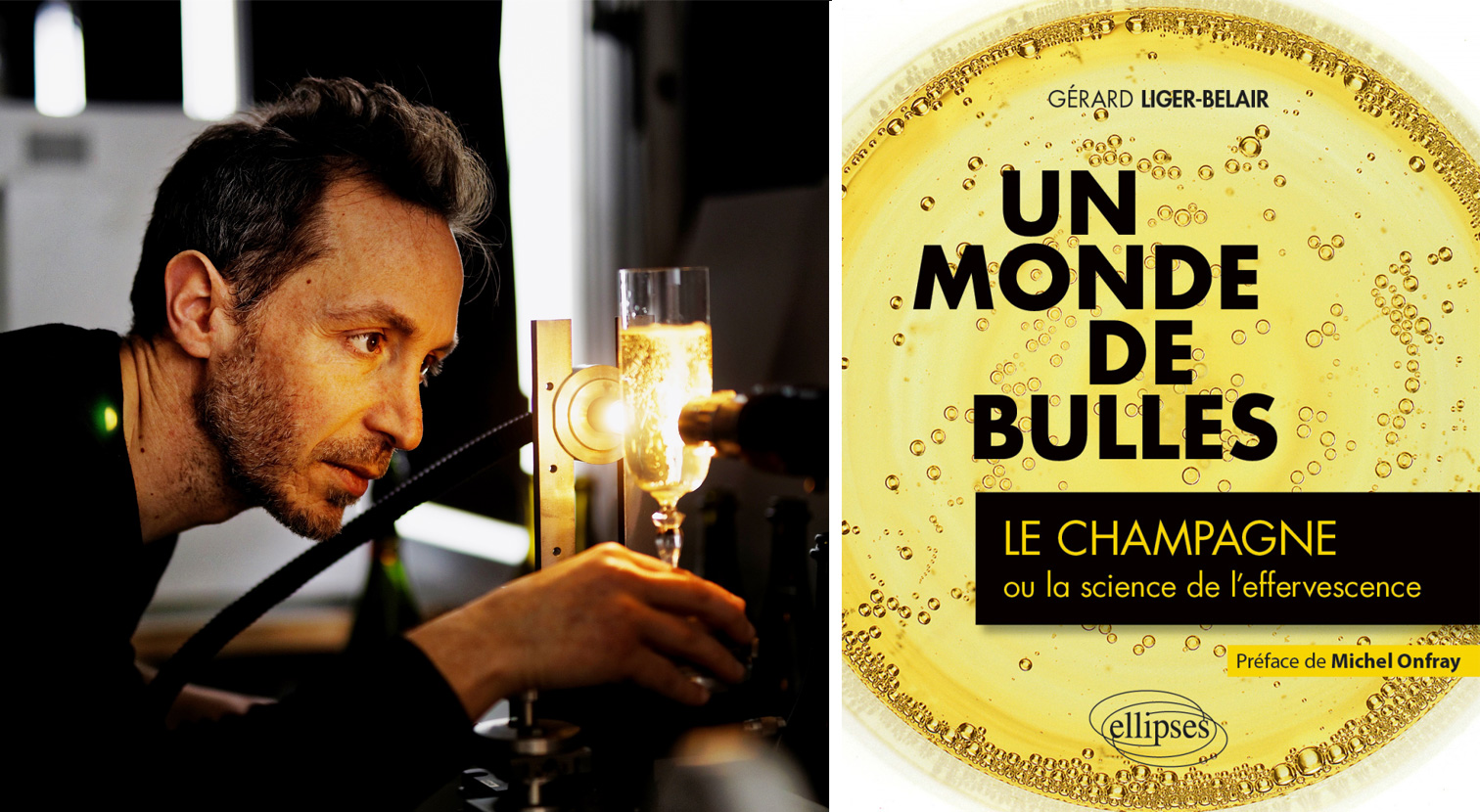

Gérard Liger-Belair, the man who straddles the line between champagne and science

Gérard Liger-Belair, professor of physics and “Effervescence, Champagne and Applications” team lead at the University of Reims-Champagne-Ardenne in France, is the only researcher in the world to specialise in champagne bubbles. He is set to join us as a Consultant for the Advanced Studies in Gastronomy (HEG) programme in June, when he will share his discoveries and insights into all the processes involved in the formation of champagne’s trademark bubbles, from the moment of production to the moment of consumption. Today, he explains what some of his work involves, and what students will explore during his “Dynamics of champagne bubbles” course.

What is a champagne bubble researcher, exactly?I may be passionate about wine, but I’m neither a winemaker nor an oenologist by trade ¬¬– I actually trained as a physicist. I’ve always had a fascination with observing natural phenomena. They obey some of the key laws of physics that have been brought to light over the past few centuries. That is exactly what can be said of the effervescence observed in champagne and sparkling wines. The bubbles form and move according to often complex equations, which allows us to anticipate a certain number of elements that influence the drinking experience, such as the number of bubbles that will be produced, their size, the speed with which they will rise to the surface, and the way in which they will burst and disperse the wine’s aroma. After presenting my doctoral thesis in 2001, I was initially appointed as an associate professor at the University of Reims in 2002, before eventually going on to become a full professor in 2007. In 2012, my colleague Clara Cilindre (a trained biochemist) and I decided to set up a team specifically dedicated to studying the phenomena behind effervescence and foaming in sparkling beverages (making the effervescence of champagne our primary focus).

You’re going to be leading the “Dynamics of champagne bubbles” course. Could you tell us a little about what the students will be exploring?The idea is to invite the students to take part in a virtual champagne tasting session, which draws on the scientific results we have obtained over the past couple of decades to present the experience from a scientific standpoint, from popping the cork right through to the bubbles fizzing in the glass. During the 1½-hour course, I will paint the most exhaustive picture possible of the various phenomena involved and of the role dissolved carbon dioxide and bubbles play when producing and drinking champagne.

Why do you think champagne is so well loved in France and, indeed, worldwide?I would say that champagne is so well loved primarily because of its bubbles, as that is effectively what sets it apart from still wines. But two additional factors also underpin its success. Firstly, the fact that the Champagne region began producing sparkling wine over three centuries ago. That gives us the benefit of hindsight, enabling us to build on previous generations’ experience and hard work to create a truly outstanding product. Then there’s the terroir, which is equally important. The climate, soil and subsoil in the Champagne region boast all the necessary properties to produce outstanding sparkling wines. That being said, some excellent sparkling wines are produced in other parts of the world, too.

How do you recognise a good champagne?That’s a particularly complex question, and one that I actually struggle to answer. What I consider to be an exceptional champagne may be less well appreciated by someone with different affinities, tastes and preferences. There are endless types of champagne, depending on the grape variety or blend of varieties selected by the winemaker, the range of reserve wines that are available to be added to each blend, the geographic origin of the grapes, the quality of the harvesting, the vintage effect, and so on.

Drinking a sparkling wine is a highly “multifactorial” experience, far more so than with still wines. Sparkling wine has an additional dimension that comes from the carbon dioxide, and consequently the bubbles. On top of that, above and beyond the intrinsic qualities of the wine itself, the choice of glass is absolutely crucial. The glass plays a pivotal role in delivering a pleasurable drinking experience. Glasses can elevate a wine or prevent it from revealing its very best traits if their geometric characteristics are mismatched to the choice of wine. I personally prefer champagnes that have had time to age, as their empyreumatic aromas become more developed and there is marginally less carbon dioxide, which makes for slightly finer, more subtle bubbles. And as is the case for wine and good food in general, good champagne must be drunk in good company. The enjoyment will be even more intense. What I will say, however, is that you can’t make an exceptional champagne unless you have exceptional ingredients. For a champagne to be good, it must have been made with healthy grapes.

What are you currently working on?My team and I are currently working on a range of topics. Something we’ve already been researching for several years is the shape of the glassware, and more precisely how a glass’s geometry and various drinking parameters affect effervescence and the release of carbon dioxide and aromas into the space at the top of the glass. 25 years ago, tall, narrow champagne flutes were all the rage. We’ve now realised, however, that when it comes to champagne, glasses that shape don’t actually deliver the best possible drinking experience. Today, the trend is shifting towards glasses that are more tulip-shaped and wider rimmed than a few years ago, with objective findings driving that shift. An increasing number of champagne houses are, indeed, asking for our input when designing their own glasses. One such example would be Moët & Chandon, with whom we have recently collaborated to design their signature glass.

We are also currently researching the topic of aromas in general. The aromas of champagne, for example, change quite considerably with ageing. We are notably trying to identify which aromas will be best perceived by drinkers when the ballet of bubbles bursts on reaching the top of the glass.

Another topic we are examining is the phenomenon of “gushing”, which is when excessive quantities of bubbles and foam are produced on opening a bottle. When the cork is popped, a powerful jet of champagne can suddenly spurt out, emptying the bottle of over half of its contents, which is extremely irritating for the consumer.

What are you hoping to pass on to the Advanced Studies in Gastronomy (HEG) students?My aim is to make the students realise that drinking champagne stimulates all the senses. I notably intend to use high-speed imagery, which has come on in leaps and bounds over the past few decades, to help them understand the key scientific principles and processes that come into play when making and drinking champagne. On completing this module, they’ll probably never look at a champagne flute in the same way again.

Uncorking the science behind the sparkle is lots of fun!